Musical Settings of the Song of Songs

by ALEX WEISER

—Shir Hashirim: King Solomon’s Song of Songs in די אלמנה Di almone “The Widow” (1908)

When Anshel Schorr wrote the lyrics for a love song between Kalman Juvelier and Regina Prager, stars of the 1908 Kalich Theater production די אלמנה Di almone “The Widow,” with music by the composing duo Perlmutter and Wohl, he looked to his traditional Jewish education, and started the song off with a nod to שִׁיר הַשִּׁירִים Shir hashirim, The Song of Songs. The show was a great success, and a few years later Schorr turned again to Shir hashirim, writing an entire operetta with composer Joseph Rumshinsky called “Shir hashirim: Song of Love” (1911), an even bigger success that would be adapted into a film in 1935.

Schorr’s invocation of Shir hashirim here is far from unique. Sholem Aleichem’s character Shimek, from his story Shir Hashirim (1909-1911), is reminded of Shir hashirim when he looks at his friend Esther Libe, and fantasizes about wooing her with the words of the Song. Writing in Hebrew, Chaim Nachman Bialik also references Shir hashirim in most of his love poetry; the Song has, in fact, been a source of inspiration for generations of Hebrew love poems.

The Song’s resonance as a symbol of love is clear, but from this perspective, its place in the Biblical canon is perhaps a bit curious.

—Mishna Yadayim (3:5)

Paradoxically, Shir hashirim, what Rabbi Akiva calls “the holy of holies,” is one of the only texts in the Hebrew Bible which has no mention of God. Rather, this ecstatic, erotic book, found within כְּתוּבִים ketuvim writings, seems to take its place within the biblical canon as the ur-love poem, or rather a collection of love poems.

Its date of composition is not certain, but its language and vocabulary suggests creation during the Post-Exilic period, sometime in the 3rd Century BCE. While it bears an attribution to King Solomon, this is generally accepted by biblical scholars not to be literally true. Some believe the Song’s anonymous writer may have been a woman because the Song’s protagonist is a strong and individual woman. The Song also portrays a matriarchal world view, referring numerous times to בֵּית אִמִּי beyt imi “my mother’s house,” with no similar mention of a father’s house, as is common elsewhere in the Hebrew Bible.

The little that we know about the origins of the Song notwithstanding, its original purpose and meaning remain elusive. Comparisons to other other ancient near Eastern texts support the notion that it is love poetry, perhaps meant for courtship, or recitation at weddings. Most of Rabbinic tradition, however, fervently denies this use of the Song.

—Tosefta Sanhedrin (12:5)

The Song has thus been understood by Rabbinic Judaism as an allegory for love between the Jewish people (the female protagonist), and God (her lover). Similarly, Christian readings have read the Song as an allegory for the Church and Christ. The Kabbalistic tradition reads the Song as an allegory for the male and female components of God.

In many Jewish communities the Song is read on the Shabbat during Passover, connecting the Song’s springtime setting with that of the story of the Exodus from Egypt. Echoes of the Song are also heard in the famous Friday evening prayer, לכה דודי Lekha dodi “Come, My Beloved,” which originated as a poem by the 16th-century poet and kabbalist שלמה אלקבץ Shlomo Alkabetz. Some communities customarily recite the entire Song every Friday.

It is also not uncommon for excerpts of the Song to be recited at Jewish weddings, especially the famous line אֲנִי לְדוֹדִי וְדוֹדִי לִי Ani ledodi vedodi li “I am my beloved’s and my beloved is mine.” The Song’s use at weddings can be understood as stemming from its literal meaning—in contradistinction to Rabbi Akiva’s warning—or perhaps as an allegory where the bride and groom’s love is understood to be as holy as the Jewish people’s love for God and as intense and embodied as the love of the lovers in Shir hashirim.

Rashi begins his commentary on the Song with an attempt to reconcile the unavoidable literal meaning of Shir hashirim with its allegorical interpretation.

—Rashi, Commentary on Shir hashirim

With deep ambiguities and a rich history of reinterpretation, the Song has been a powerful source text that many have returned to for a connection to something ancient, and in many cases for a decidedly Jewish grounding that can be adapted to fit the needs of a particular time and place. It is exactly this that we see on display in myriad ways in the variety of musical readings of Shir hashirim on this program.

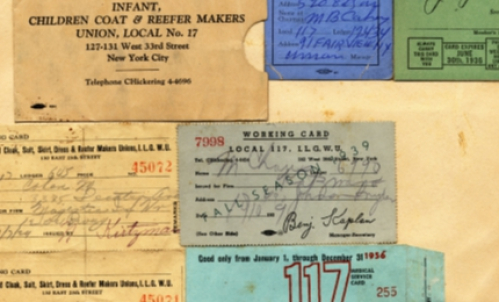

A listing for a performance of Di almone in 1908 in the Yiddish newspaper Di varhayt boasted that in this new operetta on the Yiddish stage, the audience would hear “emes idishe muzik, emes idishe handlung” (true Jewish music, true Jewish action). Similarly a flyer advertising the film Shir Hashirim: A Love Story in 1935 advertised, “The most beautiful 100 percent Jewish All-Talking Picture ever filmed.” The songs from these shows, as well as the other Yiddish theater songs on this program, invoke Shir hashirim as a symbol of divine and true love. That this symbol also has a deep and ancient Jewish yikhes allows these songwriters to create a strong sense of Jewish particularism while writing songs that in many other ways serve a community rapidly acculturating into American society.

On the Yiddish stage this symbol probably originated in Avrom Goldfadn’s Old World 1880 operetta Shulamis, whose protagonist shares a name with the Shulamit of Shir hashirim. The connection is invoked by Avsholem, the male lead, to paint Shulamis’s desirability as regal and historic.

For composers of the Society for Jewish Folk Music (an organization founded by Jewish students of the St. Petersburg conservatory in 1908 dedicated to cultivating a pointedly Jewish way to contribute to European art music), the Song similarly offered the ambiguity necessary to walk a fine line between the particularity of Jewish identity and the project of abstraction and universalism in European art music. The two works by Lazare Saminsky on our upcoming program, Sweet Is Thy Voice: The Song of Songs in Concert, exemplify some of the range of this musical project. One song, from a cycle utilizing melodies Saminsky collected visiting the Georgian Jewish community in the Caucasus, recreates a purportedly ancient folk rendition of Shir hashirim. The approach frames Shir hashirim through an ethnographic lens that can inspire classical compositions—a Jewish variant on the kind of work Hungarian composer and ethnomusicologist Béla Bartók did. The other song, from Saminksy’s Second Hebrew Song Cycle, sets a Russian-language poem by non-Jewish Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, framing the song as at once Jewish and Russian. Another interesting thing to note about this song and the Mikhail Gnesin song in our program, is that they each come with singable translations in multiple languages (the Saminsky has Russian and English, and the Gnesin has Hebrew, Russian, and German) highlighting the multifaceted identities at the root of their musical projects.

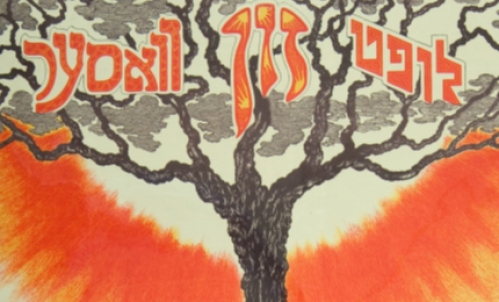

The use of Shir hashirim as an important source text extends to many other contexts as well. In her book, Agnon's Moonstruck Lovers: The Song of Songs in Israeli Culture, Ilana Pardes offers a compelling account of Shir hashirim in Israeli society of the 1920s-1950s as an example of engaging with the Hebrew Bible through the lens of a new “biblical literalism.” This “literalism,” however, in fact introduces new allegories for reading the Hebrew Bible, and particularly for Shir hashirim, as an allegory for history or for the relationship between the Jewish people and the land of Israel.

Shir hashirim was an extremely popular text to set in Israel during the 20th century. In the realm of folk and popular settings Pardes compiles a list of over 100 songs during the 1930s-50s alone, and this doesn’t include the many classical composers in Israel, including Mordecai Seter, Mark Lavry, Mordecai Sandberg, Yizhak Sadai, Ami Ma'ayani, Noam Sheriff, Dov Selzer, and many others who wrote cantatas, oratorios, concertos, chamber music, and more inspired by this ancient Israelite poetry.

In our own times, composers and songwriters continue to turn to Shir hashirim for inspiration. In 2015 Jerusalemite Victoria Hanna, released a new album of songs in an almost undefinable genre which she calls Kabbalistic Rap, overflowing with quotations from Shir hashirim. John Zorn’s 2008 30-minute wordless Shir hashirim for 5 female voices brings the Song in another direction, also perhaps unlike any other in its long history: an ecstatic avant-garde work, at times reminiscent of Morton Feldman’s 3 Voices (1985).

David Lang, whose Just (after song of songs) is also featured in our upcoming concert, has turned to Shir hashirim twice, creating his own texts adapted from it. In Just (after song of songs) Lang’s text extracts all that is attributed to one or both of the lovers into a new minimalist lyric which simply takes account of everything adding the attributions “just your,” and “my,” and “our.” As simple and material as the resulting text is, it remains perplexing and inspiring when heard in dialogue with the traditional allegorical understanding of Shir hashirim.

Shir hashirim, in its multiplicity inhabiting fantasy and reality, dream and wakefulness, public and private, earthly and divine, continues to offer endless possibilities to its readers.

Join us on December 6th to hear many of the ways Shir hashirim has inspired musical compositions. The concert will include music by classical mainstays Claudio Monteverdi and J. S. Bach, David Lang, NYC Yiddish Theater composers Joseph Rumshinsky, Manny Fleischman, Arnold Perlmutter, and Herman Wohl, and composers affiliated with the Society for Jewish Folk Music, Mikhail Gnesin, Lazare Saminsky, Jacob Weinberg, and Lyubov Streicher. The program is capped off with newly commissioned works from New York-based composer Loren Loiacono, and London-based Israeli composer, Na’ama Zisser.

Alex Weiser is YIVO’s Director of Public Programs.

FURTHER READING

Alter, Robert. (2015). Strong As Death Is Love: The Song of Songs, Ruth, Esther, Jonah, and Daniel, A Translation with Commentary. W. W. Norton & Company.

Bloch, Ariel; Bloch, Chana (1995). The Song of Songs: A New Translation, With an Introduction and Commentary. Random House.

Brettler, Marc Zvi. (2007). How To Read The Jewish Bible. Oxford University Press. Carmi, T. (1981). The Penguin Book of Hebrew Verse. Penguin Classic.

Falk, Marcia. (2004/1977). The Song of Songs: Love Lyrics from the Bible. Brandeis / Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Gorali, Moshe (1993). The Old Testament in Music. Maron Publishers. Gradenwitz, Peter (1996). The Music of Israel: From the Biblical Era to Modern Times. Amadeus Press.

Loeffler, James (2010). The Most Musical Nation. Yale University Press. milkenarchive.org

Pardes, Ilana. (2013). Agnon’s Moonstruck Lovers: The Song of Songs in Israeli Culture. University of Washington Press.

Quint, Alyssa and Robboy, Ron, eds. (Forthcoming). Goldfaden’s Shulamis: A Critical Edition. Dusseldorf University Press.

Slobin, Mark. (1990). Tenement Songs: The Popular Music of the Jewish Immigrants. University of Illinois Press.

Walfish, Barry Dov. (2018). Song of Songs: The Emergence of Peshat Interpretation. TheTorah.com

Zylbercweig, Zalmen comp. and ed. (1931-1969) Leksikon fun yidishn teater, vol. 1-6. Hebrew Actors Union of America.

ARCHIVAL SOURCES

YIVO Archives RG 112: Music

YIVO RG 37: Jewish Music Societies